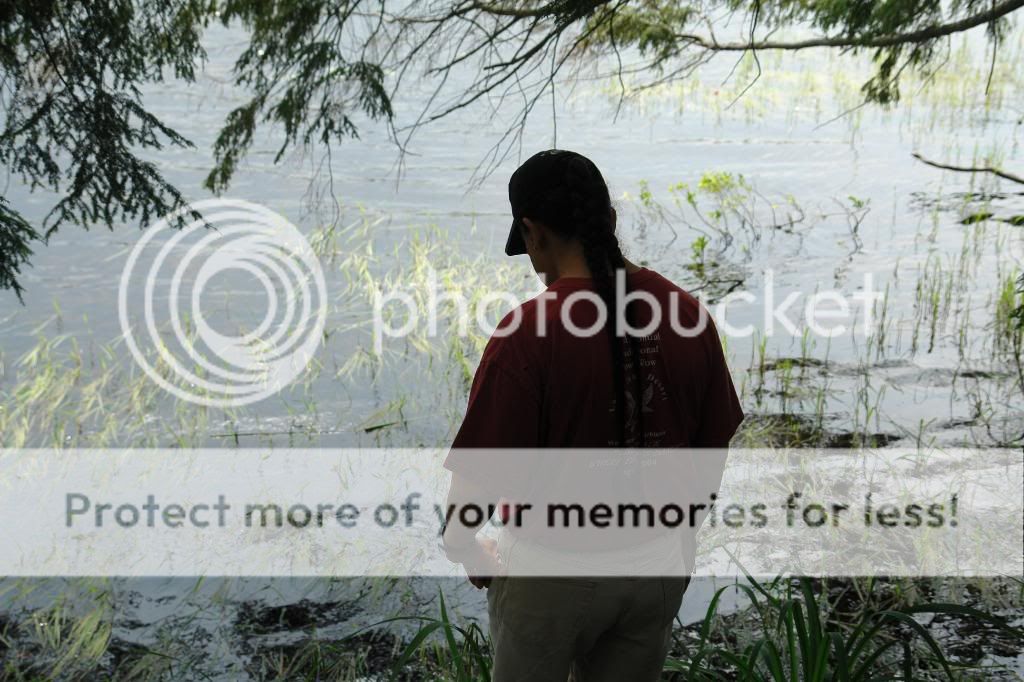

Native American guide Don Chosa points out wild rice beds to his son, one of six children whom will continue the family tradition of harvesting wild rice each September.

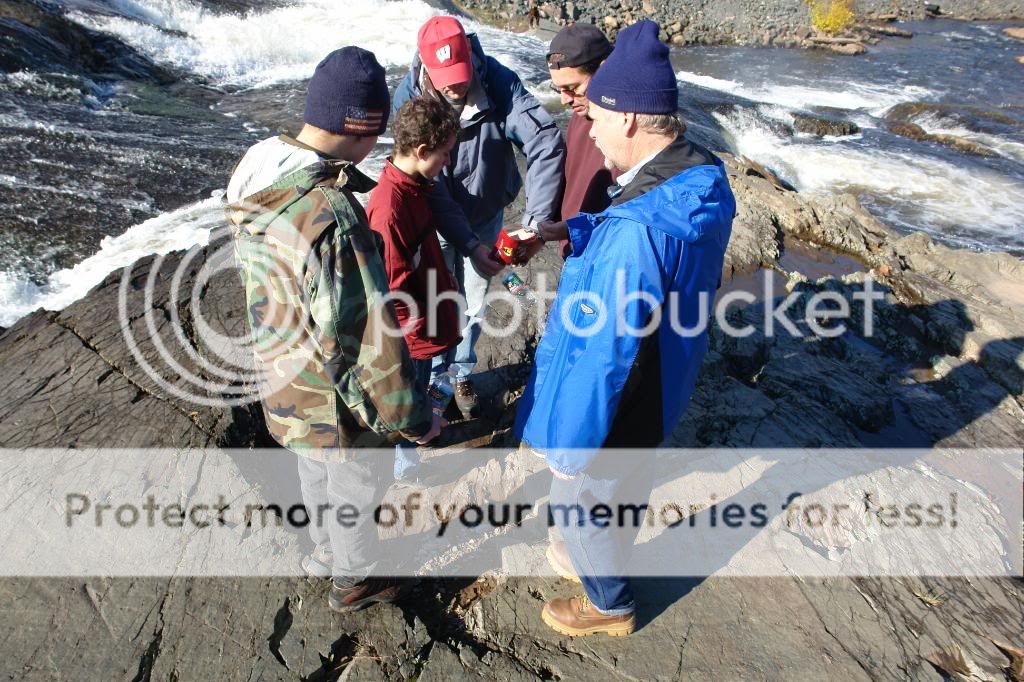

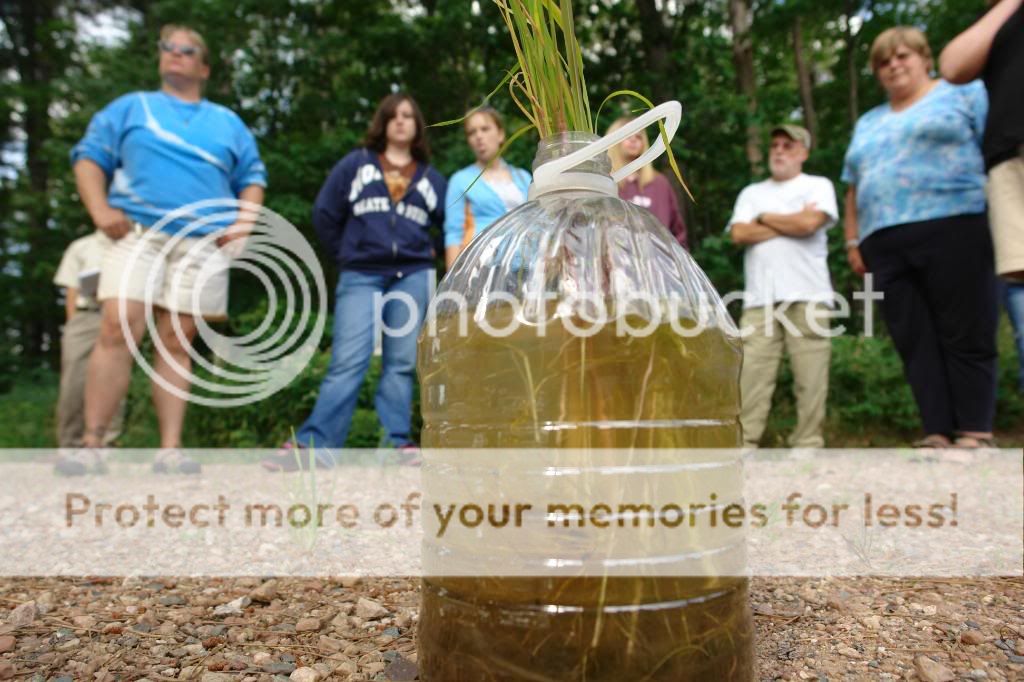

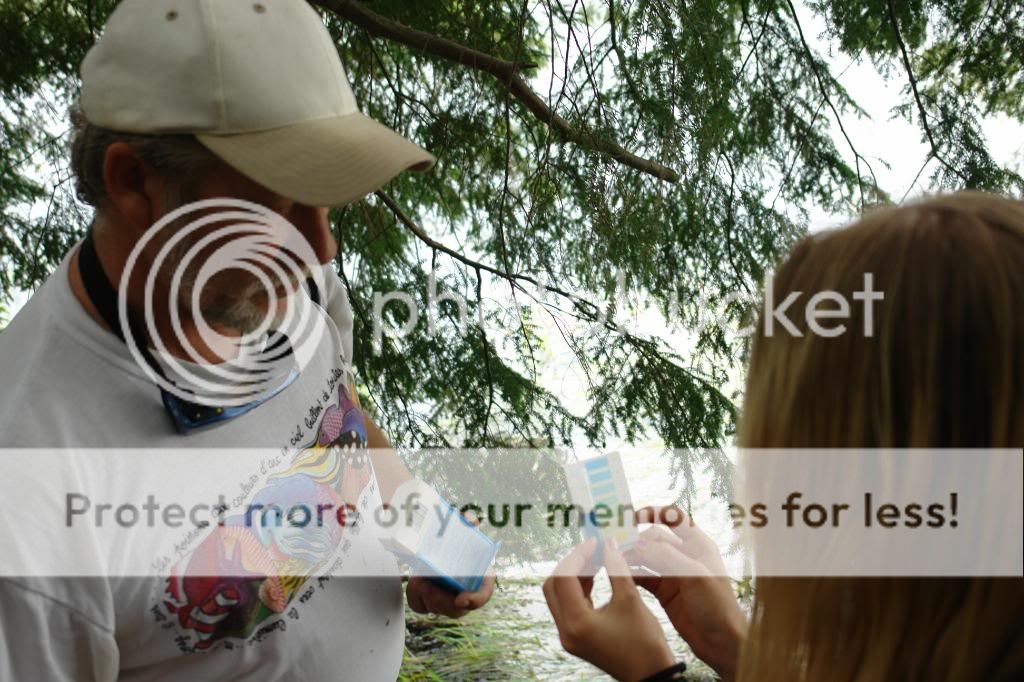

Northern Michigan teens take water samples during a survey of the previous year’s crop

At-risk teens restore wild rice to Michigan with help from American Indian tribes: 2007 wild rice planting delayed six weeks due to record drought, low water levels, unavailability of seed

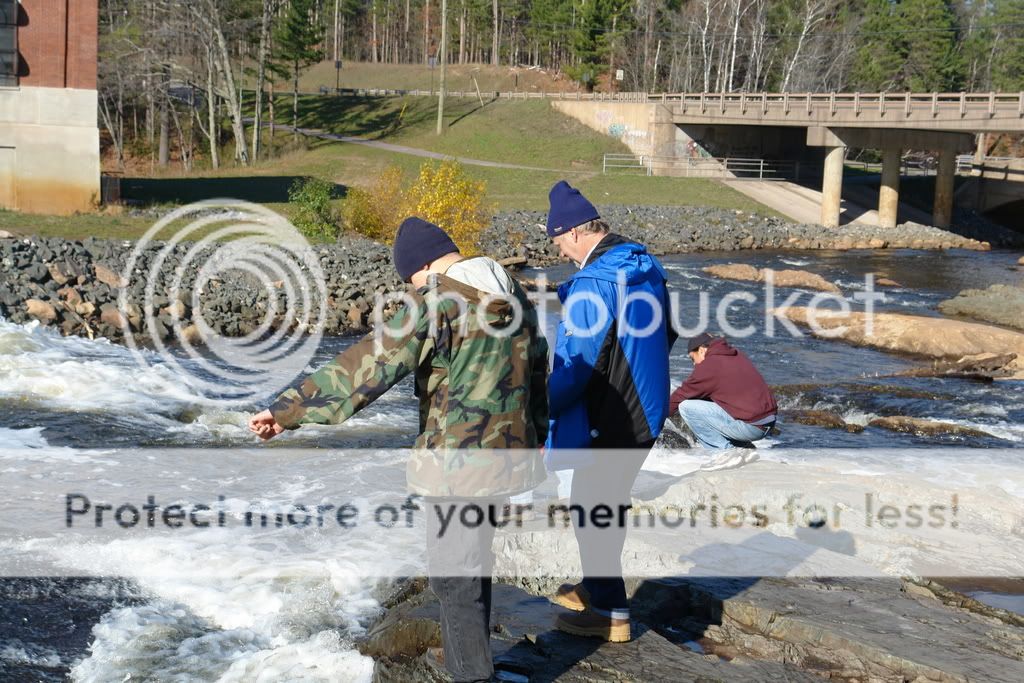

Danny Carello, 13, of Ishpeming “broadcasts” or spreads wild rice seeds into the Dead River near Marquette, Michigan during the Nov. 3, 2007 fourth annual planting of the grain that was delayed due to the extreme drought and planted only 48 hours before the first winter storm of the season dumped a foot of snow.

Manoomin Project Photos by Greg Peterson, Steve Durocher and Samantha Otto

(Marquette, Michigan) – Delayed six weeks due to extremely low water levels, teenagers, an American Indian guide and volunteers on Saturday held the fourth annual planting of wild rice in a project aimed at restoring the once abundant grain to northern Michigan.

The groundbreaking Manoomin Project has teamed hundreds of at-risk teens with American Indian guides who have planted over a ton of wild rice since the summer of 2004.

Manoomin means wild rice in Ojibwa.

Wild rice disappeared from Michigan over a century ago and is a vital part of Native American ceremonies and traditions.

Wild rice experts say the grain contains seven to nine primary medicines.

Recent studies show wild rice is an important component in reducing blood serum cholesterol and it slows or reduces diabetic blindness.

It’s also known to reduce “Seasonal Affective Disorder” or “SAD” – because it somehow gave Native American peoples the strength to survive harsh winters.

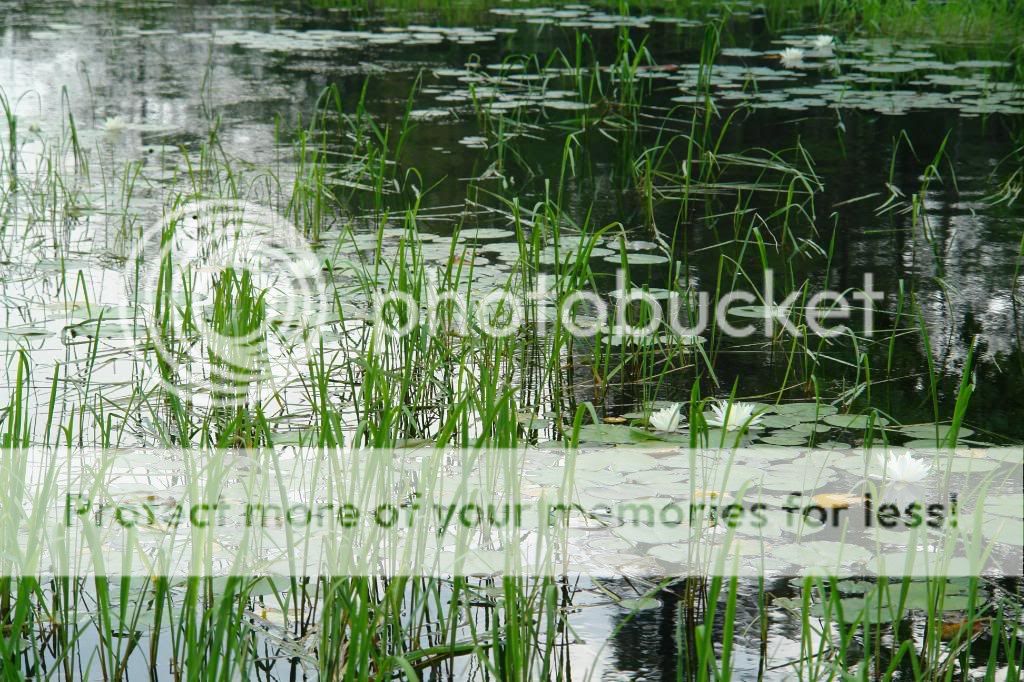

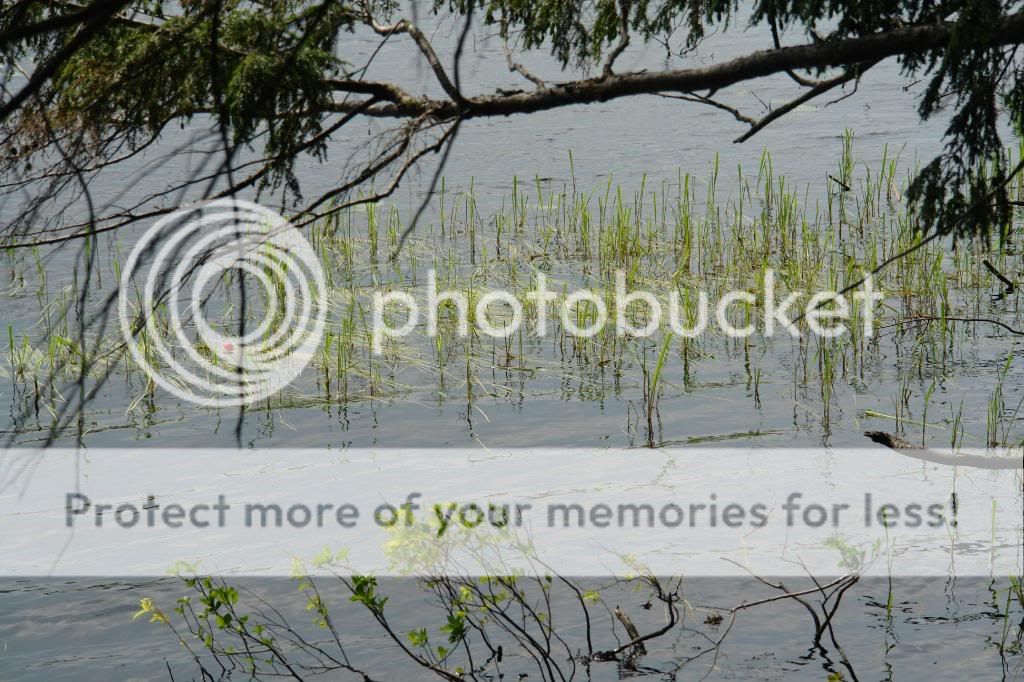

Wild rice grows with water lilies in a north Michigan wetlands that connects to a river

In northern Michigan, the grain has proven to be a powerful healing tool for young people trying to find a new path in life.

At-risk teens sentenced in juvenile court for minor crimes are restoring the once native grain to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula with help from American Indian tribes.

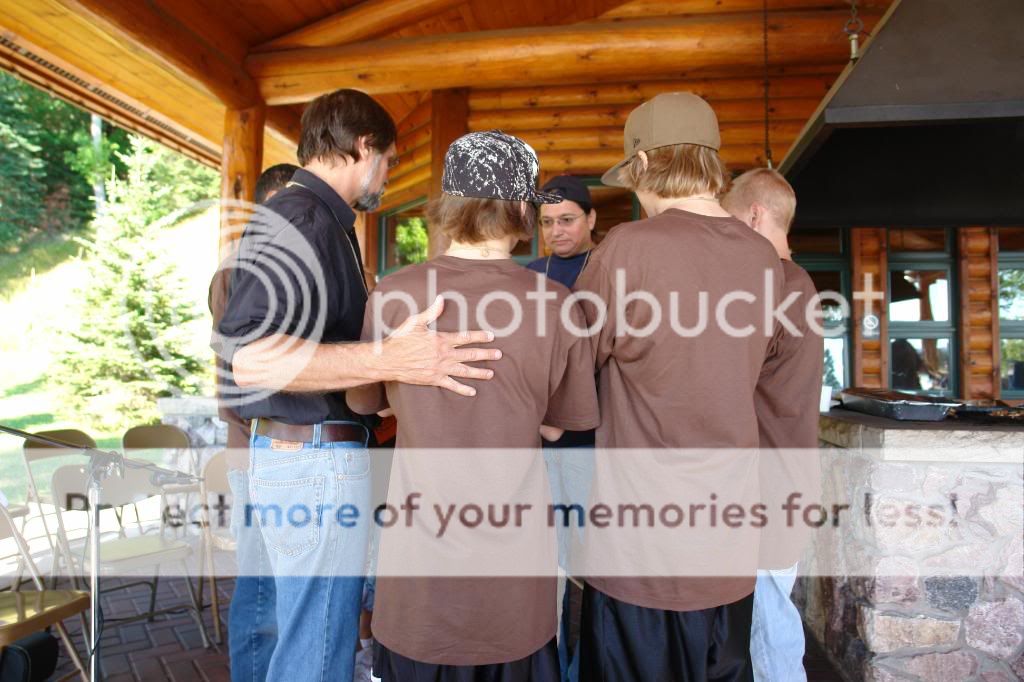

“You are the first ones to bring wild rice back to the area,” the teens were told by American Indian guide David Anthony, who has a ponytail and a calm voice.

“I am pleased that you are here and what you are doing today is very important.”

“This is very, very significant, this is a gift from the creator, it’s food grown on the water,” said Anthony, who attends Northern Michigan University (NMU) and belongs to the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa (Ottawa) Indian based in Harbor Springs, MI.

“Wild rice is the original North American grain and is very nutritious.”

Manoomin Project guide Dave Anthony teaches teens about wild rice and Native American heritage.

“This past year, wild rice across the nation kind of suffered and that worries me,” said Anthony.

“Wild rice harvesting is going down – so what you are doing becomes even more important.”

Anthony told the teens that during the harvest Native Americans carefully “bend the plants over the boat and shake and tap it – so the seeds fall into the bottom – that way they do not break the plant.”

“It’s an honor to know that you are participating in the first time wild rice has been introduced into this area,” Anthony said after the youths and volunteers sprinkled tobacco into the roaring rapids of the Dead River in a ceremony giving thanks for accepting and nurturing the seeds.

Along the Dead River in Marquette, MI on Saturday, November 3, 2007 – Native American guide says a prayer and hands out tobacco to adult volunteers and teenagers as an offering of thanks to nature for allowing the group to plant wild rice.

Pictured left to right are Shawn Molda, 15, of Gwinn; Danny Carello, 13, of Ishpeming; Marquette County Juvenile Court child care counselor Jim Rule; Manoomin Project American Indian guide Dave Anthony of Marquette who belongs to the the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa (Ottawa) Indians; and Manoomin Project volunteer Tom Reed of Marquette, who has a bachelors degree in social work.

After a blessing of thanks for the successful wild rice planting, American Indian guide Dave Anthony of Marquette, far right, kneels to place tobacco into an Upper Peninsula river that flows into nearby Lake Superior.

A Manoomin Project volunteer, Anthony attends Northern Michigan University and belongs to the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa (Ottawa) Indian based in downstate Harbor Springs, MI.

Sprinkling tobacco into the Dead River, left to right, are Shawn Molda, 15, of Gwinn; Marquette County Juvenile Court child care counselor Jim Rule and Danny Carello, 13, of Ishpeming.

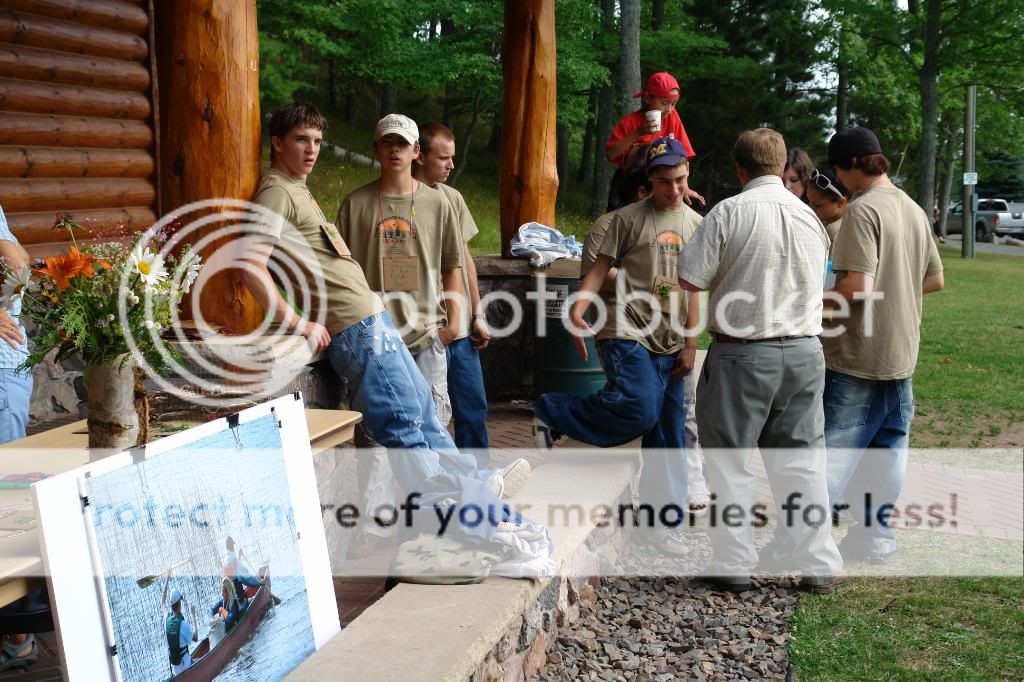

Surrounded by tall pine trees on Saturday near Tourist Park in Marquette, Native American guide Dave Anthony jokes with some of the teen volunteers while explaining why wild rice is important to American Indians.

Pictured left to right are Shawn Molda, 15, of Gwinn; Marquette County Juvenile Court child care counselor Jim Rule; Marquette County Juvenile Court probation officer Bill Mankee, and his son Michael Mankee, 3, both of Marquette; Danny Carello, 13, of Ishpeming; and Manoomin Project volunteer Tom Reed of Marquette, who has a bachelors degree in social work.

The project is sponsored by the Superior Watershed Partnership, the Cedar Tree Institute and the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community (KBIC).

Volunteer Tom Reed gave tips on planting the seeds to teenager Danny Carello during the Nov. 3, 2007 planting of several miles of the Dead River near Marquette.

“We want to give thanks to nature for allowing us to plant the rice,” said Reed of Marquette, who has a bachelors degree in social work.

“Make sure you broadcast the seed – spread it out.”

The spiritual importance of the project was not lost on the teens who picked up a few Ojibwa words.

“Megwiich,” said Danny Carello, 13, of Ishpeming saying “thank you” to nature in Ojibwa while carefully tossing wild rice seeds into a small pond along the Dead River.

Shawn Molda, 15, of Gwinn said Anthony taught the teens about the “boot” and “floating leaf” stages of wild rice.

Anthony taught a special blessing to the teenagers and adults volunteers like Marquette County Juvenile Court child care counselor Jim Rule.

After a prayer, Anthony passed out a small amount of crumbled leaf tobacco to each participant who sprinkled the flakes into the river as a symbol of thanks for the planting.

This year’s planting was delayed from mid-September because wild rice seeds were not available from Wisconsin tribes due to extremely low water levels that have had a major negative effect on this year’s crop.

On Saturday (Nov. 3, 2007) the teens planted four pales of wild rice by carefully tossing the seed into slow spots in the Dead River near Marquette.

The wild rice seeds are from Minnesota and were planted less than 48 hours before an approaching major winter storm that dumped over a foot of snow.

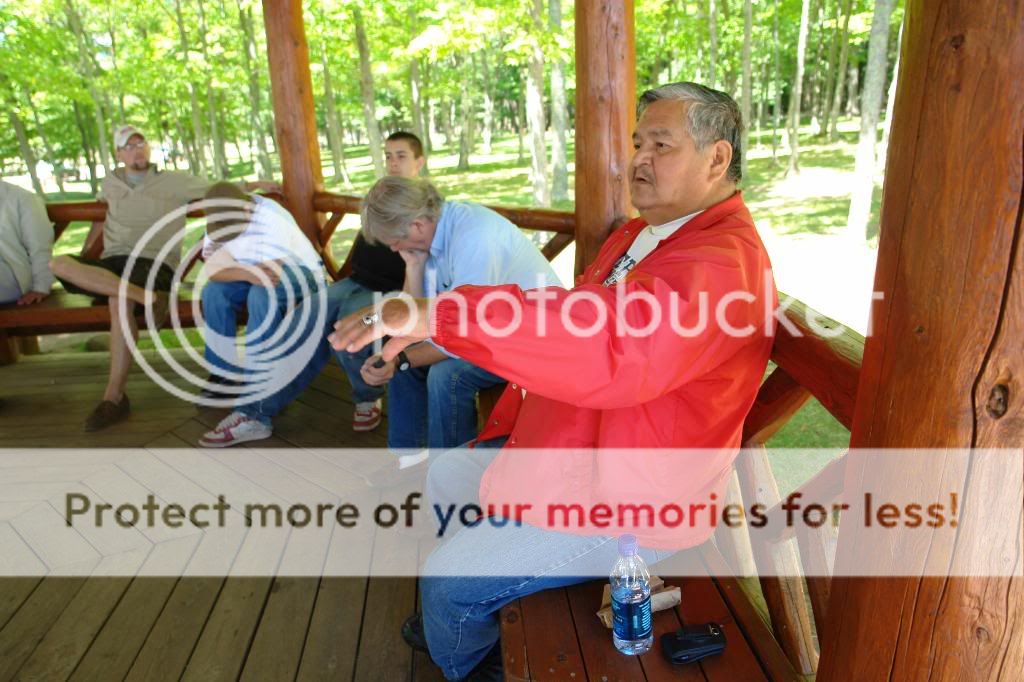

KBIC President and CEO Susan LaFernier said “the Manoomin Project is a wonderful way for this gift to continue for our generations to come.”

KBIC CEO and President Susan LaFernier speaks in April 2006 at Northern Michigan University during a press conference with the bishops/leaders of nine faith communities on behalf of the Earth Keeper Initiative student team.

“Wild rice is important to our lakes and streams and provides food for our waterfowl,” LaFernier said. “Public support is essential to ensure that we will once again have an abundance of wild rice.”

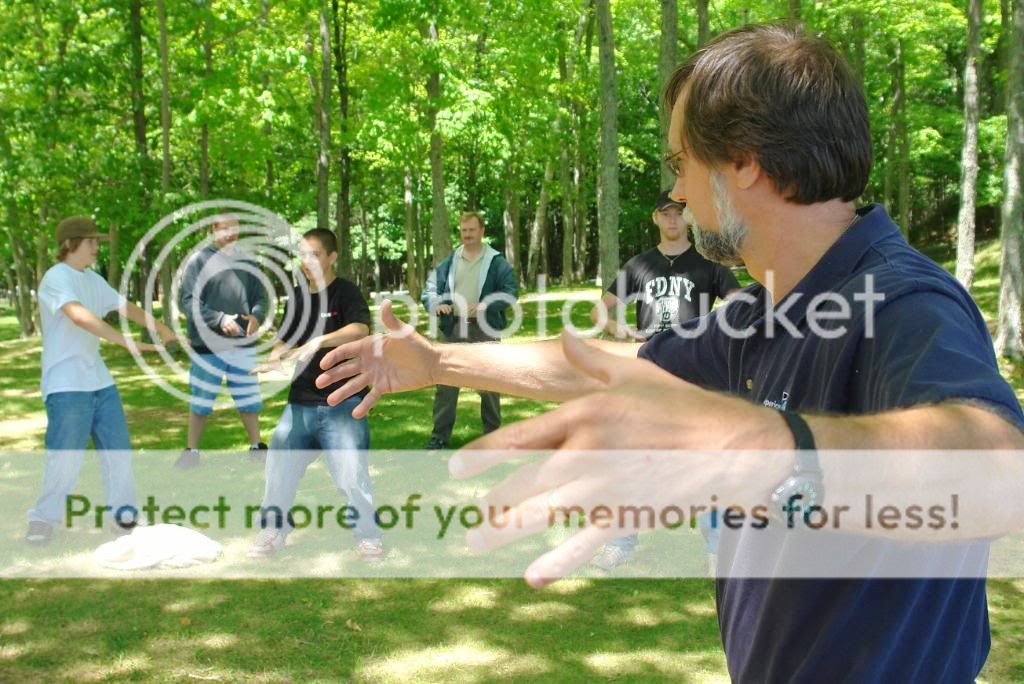

Rev. Jon Magnuson said the project is about more than planting and restoring the very important wild rice – it’s getting in touch with nature and one’s self.

“The unique dimension of this project is to bring together at-risk youth – and engage them in a restoration of a natural world,” said Magnuson, an ELCA Lutheran pastor and Manoomin Project founder who is executive director of the Cedar Tree Institute.

“There is much more going on than monitoring sites, taking water samples and planting rice, there is a healing going on with both the earth and the human spirit,” Magnuson said.

Reed said the at-risk youth volunteer to plant and study wild rice “in lieu of community service.”

Volunteer social worker Tom Reed plants wild rice on Nov. 3, 2007 in the Dead Rivernear Marquette.

“This is about educating the kids and not about punishment,” said Reed.

The record-breaking summer drought in Michigan has not created the best growing conditions for the grain, Reed said, adding seeds that reach maturity will have the harsher “weather encoded in their genetics” making it more likely the wild rice with thrive.

The teens have planted over 2,100 pounds of wild rice during the past four years at seven aquatic sites.

A favorite of food of geese and other wildlife, the sensitive crop needs perfect growing conditions to take root.

The teens are taught respect for themselves, nature and American Indian customs.

In July 2006, the teens endured rare 100-degree plus northern Michigan weather during three days of surveying the previous year’s crop.

The teens hiked several miles through the remote forests of Alger and Marquette counties documenting the how the wild rice survived the winter and hot summer.

During summer 2006 outing to survey wild rice crop, Manoomin Project teens and volunteers posed for this photo pointing out one of the best wild rice beds along an Alger County river.

It’s not uncommon for the teens to spot wildlife likes eagles, deer, waterfowl and even bears.

During that venture, the group surprised two black bear cubs as they topped a hill near one of the lakes – causing one 16-year-old girl to scream and start to run.

“Look – there are two bears,” said a teenage boy pointing at two bear cubs scrambling up a tree about fifty yards.

As the youth and other boys were about to approach the cubs, they were stopped by the soft-spoken Chosa who knew a protective mother bear was nearby.

“Remember what I said about respect,” said Chosa, a father of six children who understands youthful curiosity.

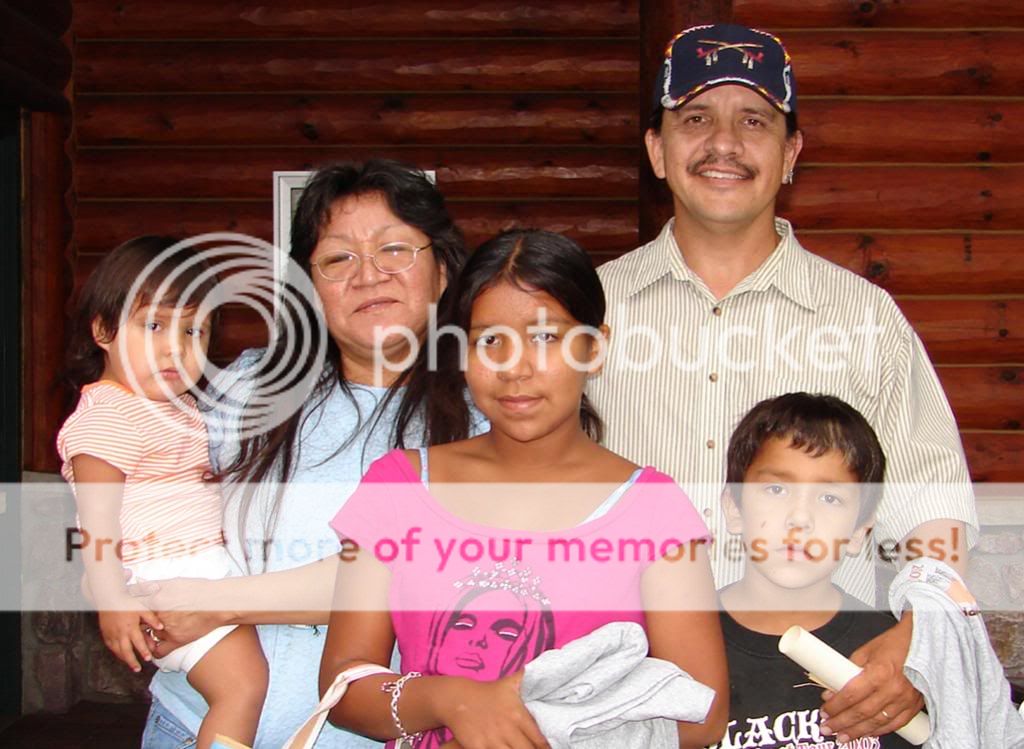

Manoomin Project American Indian Guide Don Chosa and his family in 2004 photo.

Two days later, an unexpected strong thunderstorm caused the students and the other volunteers to seek shelter at a nearby Catholic church where they took sanctuary from the pouring rain and lightening.

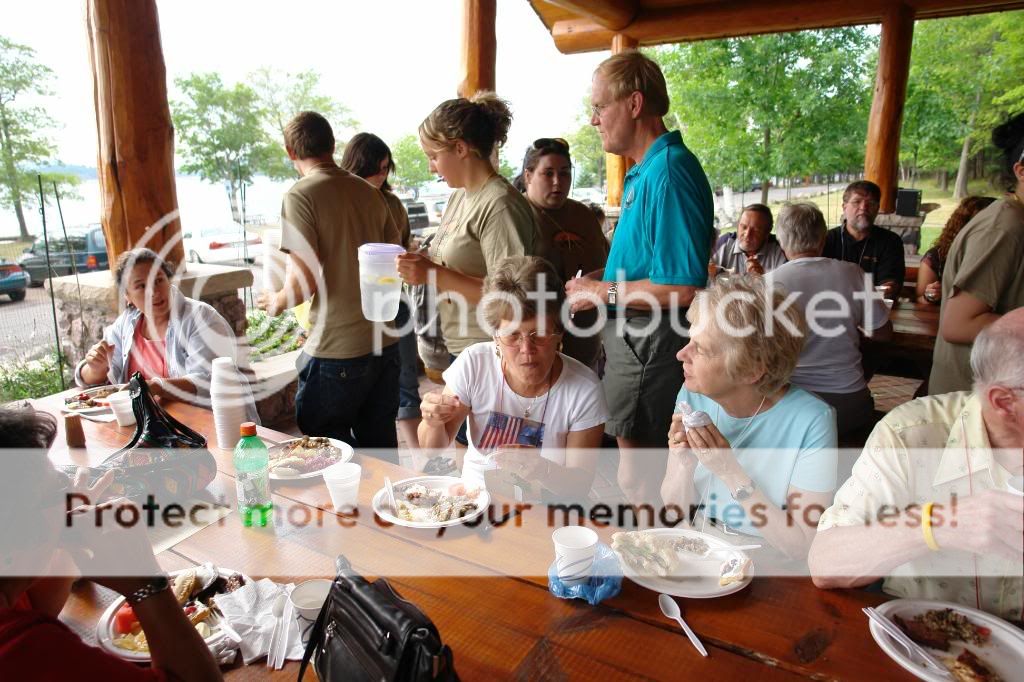

Manoomin Project teens and volunteers eat lunch at the St. Louis the King Catholic Church near Marquette during a fierce thunderstorm that popped up during 100-degree weather as the group surveyed wild rice crop

The church employees were surprised but more than happy to allow the students to get out of the storm and use the restroom and dining facilities where they ate lunch.

The St. Louis the King Catholic Church in Harvey, Michigan had the Earth Keeper Covenant hanging on the wall, a pledge signed by the leaders of nine faith communities in 2004 pledging to do environmental work and to reach out to U.P. Indian tribes.

Manoomin Project teens are welcomed at a Catholic church – that had an Earth Keeper Initiative pledge document hanging on the wall – to take refuge during a thunderstorm.

Church employees were not expecting the group but welcomed all with open arms.

During Earth Keeper Initiative project, the teens learn that wild rice undergoes several stages of growth and reproduction.

This includes the “boot” stage where the rice plants resemble tall grass and protect the stalks that will grow the seed.

Wild rice also has a “floating leaf” stage during which it looks like grass mats floating on the top of the water.

“We have representatives of the KBIC tribe at every stage of the Manoomin Project including the tribe’s cultural committee, the identification and monitoring of wild rice planting sites, and rituals of tobacco and prayer,” said Rev. Magnuson. The teens are taught various tribal beliefs and customs, and have the opportunity for religious and spiritual learning – but it is not forced upon the youths.

Fifteen year-old Brooke Soeltner of Negaunee started sobbing when told her probation involved planting wild rice, but it turned out to be one of the most rewarding experiences of her life.

“I started to cry because I had to it,” recalled the Negaunee High School sophomore who quickly learned to enjoy the experience.

“But when I went there I knew a bunch of people and did not have to teach anyone about wild rice and they were teaching me and I did not cry,” Soeltner said.

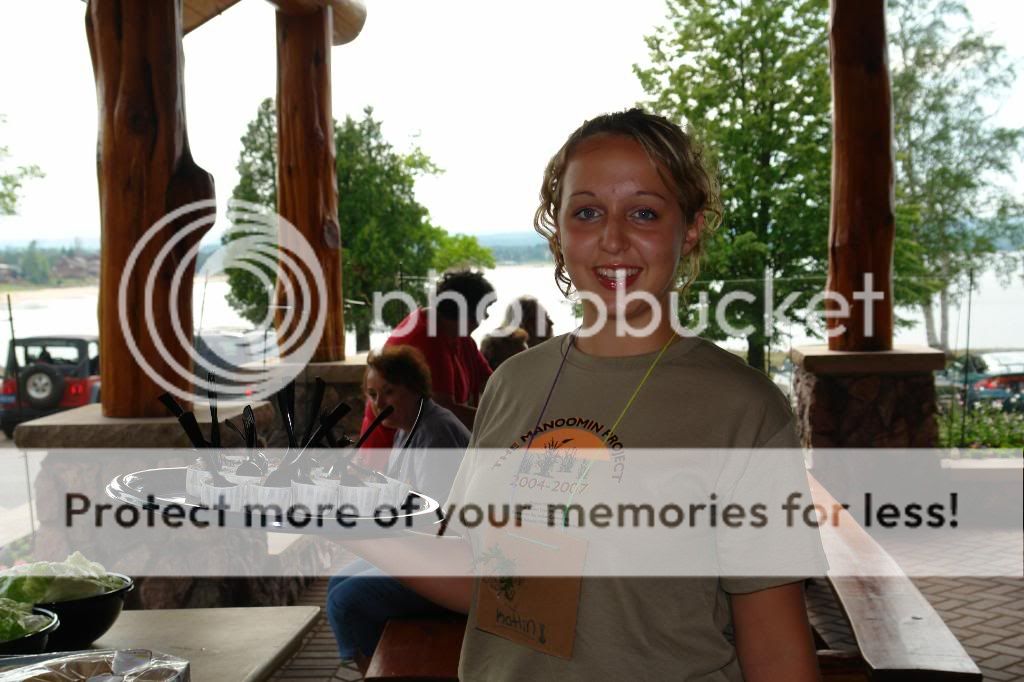

Fifteen year-old Brooke Soeltner of Negaunee cried when she first learned about participating in the Manoomin Project but quickly made friends and had fun like this July 2007 “Blessing of the Wild Rice” ceremony in Marquette, Michigan.

“We learned how to say hello in Ojibwa and that Manoomin means wild rice – it was very fun,” Soeltner said.

“I thought it was pretty cool that we got to learn about how the American Indians use wild rice and how important it is to them.” Soeltner enjoyed climbing mountains and riding in a canoe while learning how to plant and identify wild rice and other nature.

“We saw frog eggs,” Soeltner said.

Marquette Senior High School sophomore Justin McGuire was 12 years old in the summer of 2005 when he learned the different stages of wild rice and several Ojibwa words.

“Before planting the wild rice we researched it at the library and talked to Native Americans about the proper way to plant and harvest the rice,” McGuire said.

“We took the canoe and spread the rice seed.”

The Manoomin Project used canoes to plant the wild rice during normal seasons, although the late 2007 planting required a several mile hike up a Lake Superior tributary.

(Photo by Steve Durocher)

“In the beginning it seemed kind of unusual but once we got into it we realized it was a useful thing we were doing for the community,” McGuire said.

Marquette County Juvenile Court arranges for adjudicated teens to get involved in the wild rice and other nature projects instead of mindless work.

Other innovative juvenile court projects include maintaining ski trails and providing chopped firewood for the needy by clearing lots for homebuilding.

“At first it’s new and strange to the teens, but when they finally realize it okay to actually learn about wild rice they thinks it’s pretty cool stuff,” said Marquette County Juvenile Court probation officer Bill Mankee.

“We learned more about American Indian culture and the four colors of direction – red, white, black and yellow.”

“The kids have learned to make connections with the environmental and natural resources,” Mankee said.

“We are trying to get the wild rice to come back and what we can do to keep it from disappearing.” Marquette County Juvenile Court child care counselor Jim Rule said its important that “the teens are giving something back to the community and nature.”

“I think it’s a positive thing for the youth and for the Dead River after it was devastated by the (May 2004) flood,” said Rule, who works at the Marquette County Youth Home.

“It gives the kids a feeling of ownership in nature instead of mindless work that doesn’t mean anything,” said Rule, who was a probation office for 12 years.

Initially some of the teens are not happy to be planting and surveying wild rice because its part of the court process, but after getting outdoors into nature many say it was time well spent.

“Some of the teens were angry just to be there because it was something they had to do,” said Native American Don Chosa a KBIC member who recently moved back to the International Falls, Minnesota area where he belongs to the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa and the tribe harvests wild rice on pristine Nett Lake.

“But as soon as we started and the teens started learning – they started to enjoy it – and by the time they were done with one year planting wild rice they were willing to come even on a volunteer basis the following years,” Chosa said.

“We had a good time planting wild rice.” “They learn how to plant, harvest and cook wild rice and how to take water samples,” said Chosa, a father of six who taught the teens stories about the spiritual aspects of wild rice and its use in all tribal gatherings including naming ceremonies, funerals.

“A lot of them hadn’t been outside very much, so for them it was a good experience because it was miles and miles of hiking and mountain climbing.”

“Wild rice is used in all (American Indian) ceremonies including naming ceremonies, funerals and all gatherings throughout the year,” said Chosa, a former NMU Native American Studies adjunct professor who guided the first three wild rice plantings.

Since age 14, Chosa, who sports Native American earrings and a ponytail that peaks from beneath his baseball cap, has never missed helping relatives harvest wild rice every September on pristine Nett Lake surrounded by the Boise Forte reservation.

An annual “Blessing of the Wild Rice” event is held during July in Marquette to give thanks to nature for allowing the wild rice to be planted and eventually harvested.

Native American guide Dave Anthony says a prayer during the 2007 “Blessing of the Wild Rice” in Marquette.

American Indian guide Don Chosa leads the 2006 “Blessing of the Wild Rice” ceremony.

KBIC guide Don Chosa prepared an offering during the 2006 Blessing of the Wild Rice that was taken into the woods by the teens and placed behind a log as a thanks to nature.

April Lindala sings Ojibwa songs during the 2006 Blessing of the Wild Rice in Marquette.

Lindala is now director of Native American Studies at Northern Michigan University.

“We have helped plant a food that our ancestors relied on for their survival,” said KBIC President and CEO Susan LaFernier.

“Because of these plantings we can continue to enjoy this food and remember our ancestors that way.” “Manoomin or wild rice is a ‘food that grows on the water’ and through the ages has been used by all people in order to survive,” LaFernier said.

“It is believed that it is a spirit food and is a special gift to the people.”

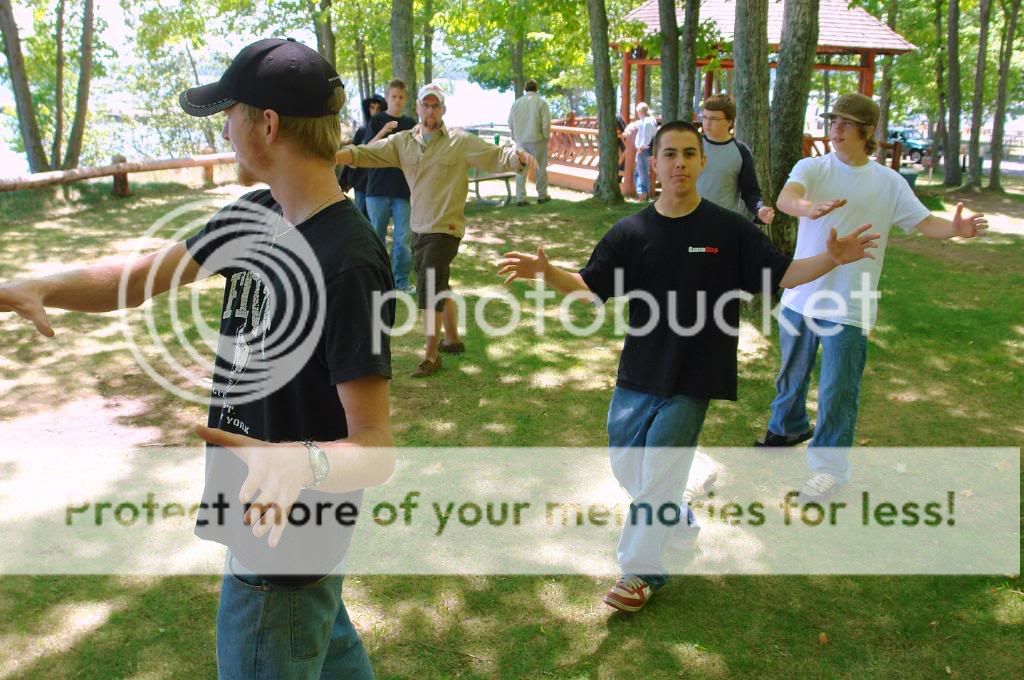

The Manoomin Project includes Tai Chi relaxation training for the at-risk teens.

Rev. Jon Magnuson leads Tai Chi exercises in July 2007 at Presque Isle near Marquette

In July 2007, KBIC elder Glen Bressette of Harvey met with at-risk teens and explained how he had similar problems when he was young but overcame issues like racism, abusing alcohol, and scrapes with the law including being shot at by police during the petty theft of gas.

“I grew up with that prejudice – I was a dirty Indian – I was a stupid Indian,” Bressette said. “I grew up in a lot of hate.”

In the eyes of local residents, “I was an old drunken Indian – I was just a dumb Indian,” Bressette said.

That hatred turned Bressette against whites.

“Drinking helped me cope with that” prejudice and hatred, Bressette said.

“After I sobered up I found out there were other things in the world than alcohol and drugs – and that was doing things for the people.”

That story touched a chord with fifteen-year-old Danny Weymouth because “I remember what Mr. Bressette went through when he was growing up – he had an alcoholic father and how he remembers harvesting the rice.”

The Ishpeming High School sophomore said he “learn a lot” from the project including “what the Native Americans went through and their culture and the importance of wild rice.”

“I remember him telling us about the four colors of the medicine wheel,” said Weymouth who participated in the project with his younger brother Bobbie, 12.

“I had ever even heard of wild rice until I started and I was surprised because I thought I knew every food that there was.”

“I have a lot of friends who are Native American and now I appreciate their heritage and culture,” Weymouth said.

“Over all I thought it was a fun project and I enjoyed spending time with the others (teens) who became my friends,” Weymouth said.

“I pretty much learned everything there was know about the wild rice and how it was grown and harvested.”

The Manoomin Project often used canoes to plant the wild rice.

(Photo by Steve Durocher)

The Manoomin Project includes classroom and library time.

“They told us how they brought the wild rice into the canoe and tapped the rice off,” he said, adding from the get go he thought the project would be fun and a learning opportunity.

In its four years, the project has had mixed success – in some areas the rice is reproducing strongly even in an unlikely pond close to town – and in other sites its not taking root like organizers had hoped.

That’s why the teens study the seven secret sites each July taking temperature, acidity and other water samples.

“Through this project we are reconnecting various strands of web of life and culture that have been disconnected – that have been torn apart – thru environmental degradation and neglect and the pursuing of selfishness have torn apart the fabric of the web of life,” Reed said.

“We provide an opportunity for the teens to reconnect with the Earth itself and as well as the Ojibwa culture and spiritual traditions,” Reed said.

“Sometimes we find that an insect or a duck or deer munched on the wild rice or fish ate it,” Reed said.

Even those setbacks to the wild rice reproduction, Reed said, “are my idea of success because we’ve reconnected these lost connections in the natural and social world and those are evidence of the success.”

Reed said planting wild rice on “the edge of its natural range is one of those elements working against us (but) we are trying to reintroduce it in a place where it naturally grew prolifically at one time.”

While project organizers are not sure why rice does well in one area and not in another – they suspect it has a lot to do with how much is eaten by wildlife who find the grain to be a sweet treat.

At one pond, pictured below, near Marquette’s Dead River, the rice unexpectedly flourished.

“The reason it worked there may be the lay of the land – it’s low and sheltered – and doesn’t provide a flyway in and out” for ducks and geese, Reed said.

“I found a rice worm in that pond – and some may say that finding a rice worm may be a bad thing because rice worms eat wild rice seeds – but I feel we have connected a broken strand,” Reed said believing it is just as important for the rice to be a food source.

“Wild rice feeds the fish and the birds – it’s reconnecting the torn elements of the web of life” that were broken since the grain disappeared from northern Michigan a century ago,” Reed said.

“I think it’s cutting-edge,” Reed said. “We are healing the Earth.”

The teens are also instructed – but not forced to participate – in non-denominational religious teachings and American Indian values about being respectful to adults, trustworthy citizens, positive role models to other youth, and good stewards to the environment.

The Manoomin Project falls under the umbrella of the Earth Keeper Initiative that is a faith-based coalition of adults, university students, and the leaders of 9 faith communities with 140 church/temples.

The KBIC participates in all Earth Keeper projects that include an annual “clean sweep” that has collected about 370 tons of household poisons and other waste that was turned in by about 15,000 U.P. residents at dozens of sites across northern Michigan on the past three Earth Days.

The Manoomin Project brings together northern Michigan’s white and Native American communities to break bread and honor nature.

The annual Blessing of the Wild Rice includes native foods, songs and ceremonies.

The northern Michigan teens learn to care about others, themselves and nature.

Looking at these polished teens it’s hard to believe they are considered “at-risk.”

Many say they have learned a lot from their experience with Native Americans and nature.

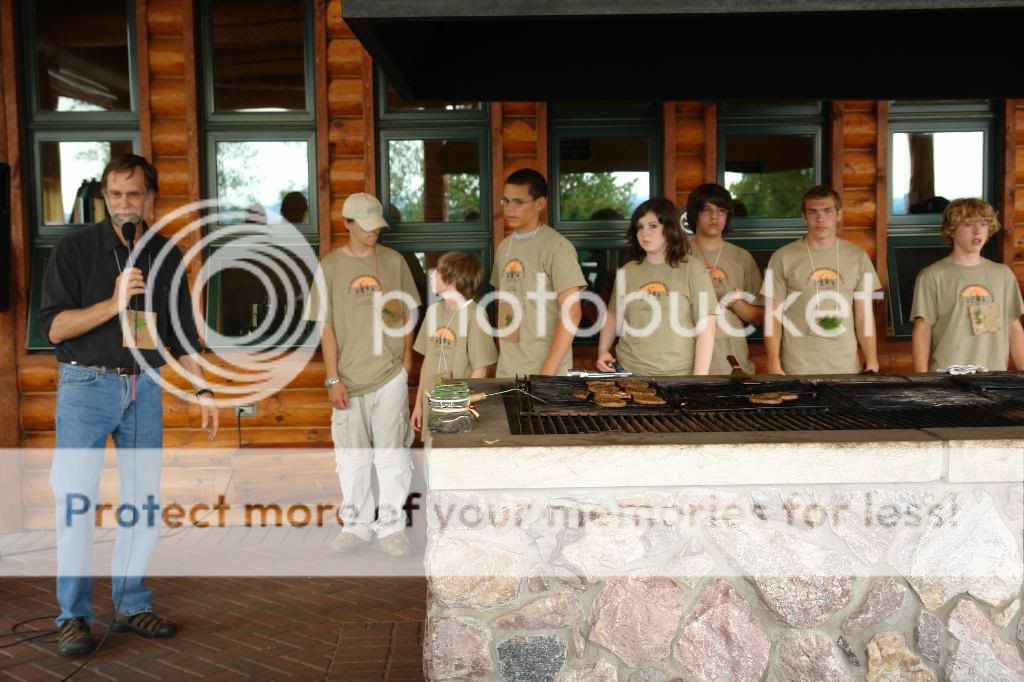

Manoomin Project founder Rev. Jon Magnuson, above, introduces the teens to the crowd during 2006 Blessing of the Wild Rice.

As northern Michigan teens embark down the long and sometimes dangerous road of life, they take with them Native American knowledge learned during the Manoomin Project.

That wisdom includes treating each other with kindness and respect, and honoring nature and God for all the gifts that come their way.

The End of the Manoomon Project is really a Beginning:

The end of the four-year Manoomin Project in northern Michigan closes the doors on this chapter of the wild rice resoration project but it’s the start of the road for the teens who learned valuable life lessons from their Native American guides.

Thank you to the hundreds of teens, volunteers, donors and our American Indian friends who helped make it a success.

Megwiich !